After growing somewhat accustomed to (the disappointment of) the ITABC Pinyin Chinese input method that comes with OS X, I configured my Vista work box to add the MS Pinyin input method which I soon discovered was far superior to Apple's ITABC. Partly this is due to some crasher bugs in ITABC (which I've reported and never heard back about, so maybe it only happens on my Mac?) - for example, typing any string with "shish" in it will cause part of it to crash, so that SCIM must be manually killed to force the input method system to restart before Chinese can be typed again.

More importantly however, it's just so much

easier to type in the input method for Windows. I can type a full sentence and, often enough, the whole thing will be interpreted as I intended, or the small number of corrections can be elegantly entered without deleting interceding correct characters. In the Apple ITABC method, it has a strange heuristic of trying to forcibly group pairs of characters at a time, even when two single characters are much more likely. This results in an erroneous offset which often propagates all the way through the sentence so that in practice one ends up correcting the input method every character or two (by hitting space and selecting the correct match) and/or accepting then going back and correcting input manually. Not only this, but some words like 儿 completely throw off the parser - if you type 'dianer' the result is '嗲呢日' (dia3 ne ri4) rather than the obvious '点儿'.

After using the Microsoft Pinyin IME briefly in college and coming home to be stuck with this again, I decided enough was enough, and started searching for alternative input methods. My brief search took me to OpenVanilla, something else that didn't work well, and finally "Fun Input Toy", a beguilingly-named input method which I downloaded from

here.

After installing it mostly blind because my Chinese is absolutely not good enough to run programs or read technical documents (or, eh, any documents except for kids' books really) and wincing at the Chinese-only menus, I soon got it working (because the "Next" button in the installer wasn't translated, but you know the position it's in anyway :D). I was initially impressed, but decided to keep my enthusiasm somewhat checked before jumping to conclusions. Not for long though, because it soon became apparent that writing Chinese sentences with FIT is much easier and quicker than ITABC, and it's not as buggy.

By way of comparison, here's the result of typing the string "zheshougemeiyounashougenamehaoting" in both input methods without corrections:

ITABC: 折寿个没有拿手个那么 (4/12 -> not gonna even try translating that mess)

FIT: 这首歌没有那首歌那么好听。(12/12 -> "This song is not as nice as that song.")

Note that in ITABC, once I'd typed the pinyin string, I had to hit space once to start parsing, which yields 折寿, then space again for 个, again for 没有, again for 拿手 and so on. Note that it terminates after 那么 because it only accepts input of up to 10 characters, which means breaking mid-sentence (in practice, after only a few words because the parser gets so confused).

Also note that I typed sentences like this a few times under both systems to allow any learning mechanisms to observe my use of less common words like 歌 (ge1: song).

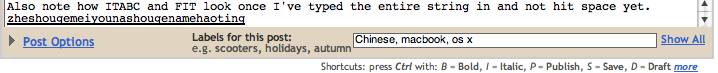

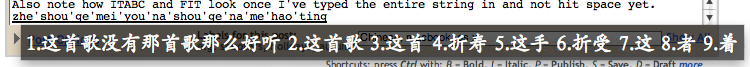

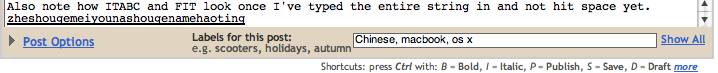

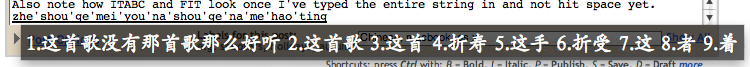

Also note how ITABC and FIT look once I've typed the entire string in and not hit space yet:

ITABC: Fun Input Toy:

Fun Input Toy:

The FIT input window clearly shows much more information (such as the fact that it parses as much of the sentence as possible, with appropriate options for corrections, compared to ITABC only parsing a couple of characters at a time; usually two).

In summary, ITABC is pretty awful, FIT is very nice. And it's free, so use it!